Reproduce information

ValiText

A Validation Framework for Text-Based Measures of Social Constructs

Last update on November 22, 2024.

1. Introduction

In this tutorial, we introduce the ValiText tool, a framework and instrument for validating text-based measures of social constructs. ValiText helps researchers to execute and document validation by providing conceptual and practical guidance for researchers (Birkenmaier, Wagner, and Lechner 2023).

Validation is a necessary requirement for any text analysis (Grimmer and Stewart 2013). Essentially, the purpose of validation is to ensure that what is to be measured (i.e., the numerical scores assigned to texts) correspond to the true1 nature of the construct being studied.

Data Quality is an important requirement for validity. Low quality data can significantly affect the validity of text-based measures. For instance, when the text data is incomplete, ambiguous, or misrepresentative, it becomes challenging to draw accurate inferences about social science phenomena. However, detecting these data quality issues can be difficult. ValiText helps researchers with a shared vocabulary denoting different validation steps, as well as practical checklists that can be downloaded and filled-out to document validation. At its core, the ValiText tool can be used for any of the following tasks:

- Defining the key types of validation evidence that are required for sufficient validation

- Guide researchers which concrete validation steps to apply for their text-based research, and

- Provide a documentation template in the form of a checklist that can be used to document validation efforts effectively.

In this tutorial, we will begin by presenting the framework (Chapter 2), followed by a practical example of its use in measuring sexism in social media posts (Chapter 3), and finally conclude with a discussion (Chapter 4).

2. ValiText Tool

Validation is a critical task in text analysis and natural language processing. At its core, validation involves various activities to demonstrate that a method measures what it purports to measure (Cureton 1951; Repke, Birkenmaier, and Lechner 2024). However, validating text-based measures can be challenging (Krippendorff 2009).

Therefore, any empirical measure needs to be validated. One crucial problem in the validation of text-based measures, however, is the lack of conceptual clarity on how to conduct validation.

To provide practical guidance for researchers and users to conduct and communicate validation, ValiText offers a flexible and consistent approach to validation.

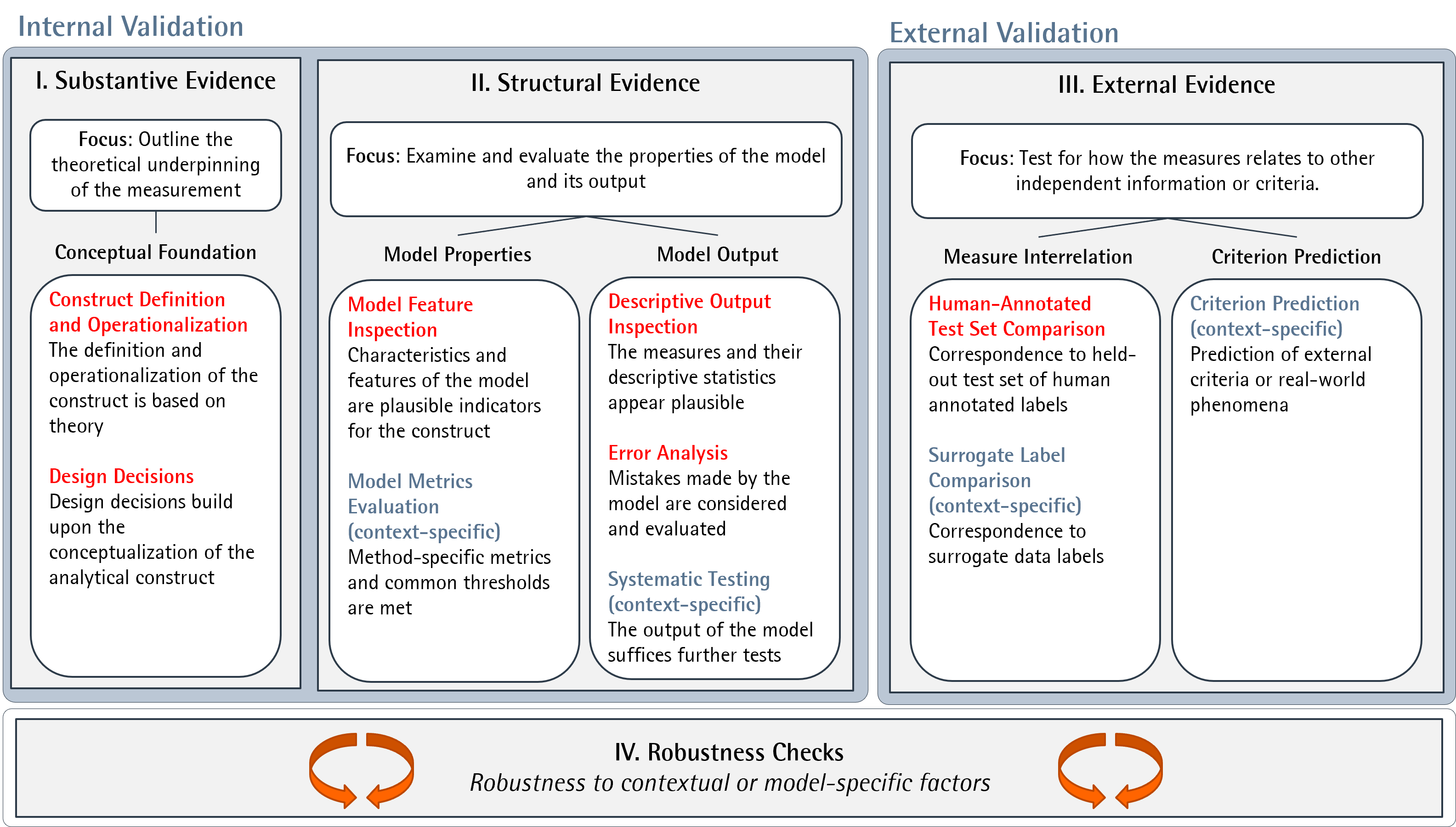

At its core, ValiText requires three types of validation evidence:

- Substantive Evidence: Requires outlining the theoretical underpinning of the measure.

- Structural Evidence: Requires examining and evaluating properties of the model and its measures.

- External Evidence: Requires testing how the measure relates to other independent information or criteria.

The framework is complemented by a checklist that defines and outlines empirical validation steps available to collect validity evidence for different use cases. For each validation step, we include its name, a brief description, implementation methods, and a classification indicating whether the validation step is generally applicable or context-dependent. Additionally, we provide references to practical applications and further literature.

If you want to learn more about the framework and the checklist, please click on the respective section below or have a look at the corresponding paper.

Different checklists are available for different use cases, depending on the text-based methods used. The table below summarises the use cases, and provides download links to the checklists

3. Application and use case

We demonstrate the applicability of the tool by revisiting and documenting the validation steps from a study by Samory et al. (2021). In their study, Samory et al. (2021) rely on different types of supervised machine learning models to detect sexist social media posts within different social media datasets.

Detecting sexism is a challenging task due to its complex nature, as sexist language often manifests in subtle and nuanced ways. In their paper, Samory et al. (2021) investigate several strategies to enhance the measurement of sexist phrasing. Since their study utilizes a labeled dataset (i.e., data with human-provided annotations), the focus lies on improving the model’s ability to classify texts, and less on exploring substantive research questions. Since their study utilizes supervised models, we completed the checklist B: (Semi-) Supervised Classification. We illustrate how the checklist can act as a documentation tool, providing a clearly structured overview over all relevant validation steps. For other use cases, the tool can also guide validation conceptually, and assist in interpreting the metrics identified during validation.

Below, we provide the filled-out checklists for each overarching type of validation evidence. In each chapter, we highlight single validation steps and how ValiText can help to document and evaluate them. The full discussion of all validation steps can be found in the corresponding paper.

Substantive Evidence

Starting with documentation of the conceptual background (I.1), Samory et al. (2021) provide extensive evidence on their engagement with the relevant literature and other sources of information. For example, the authors discuss existing definitions and attempts to measure sexism using computational methods, conclude that there is definitional unclarity, and reflect on possible biases and spurious artifacts in previous research. Moreover, they evaluate survey measures of sexism (i.e., sets of questions or statements that are used to measure social constructs) from the field of social psychology.

Afterwards, they provide a justification of the operationalization (I.2), that is, the link between their construct and the textual data. Because they primarily apply supervised machine-learning methods, the authors’ underlying justification lies in the provision of high-quality training data that enables the text model to autonomously learn and adapt relevant patterns in the data. To annotate sexism within their training data, the authors develop a detailed codebook based on four subdimensions of sexism identified in the previous literature (e.g., “behavioral expectations” and “endorsement of inequality”). In addition, they extend the codebook to not only differentiate between sexist content, but also between varying degrees of sexist phrasing. To test their operationalization using a codebook empirically, they rely on manual pre-coding (I.3) to label the sexist items from the survey scales into relevant subcategories, finding considerable agreement.

Following this initial stage of construct definition, the authors then discuss their design decisions. They outline their justification of data collection decisions (I.4), in particular using different textual datasets. They rely on Twitter data collected through various keywords and strategies and survey scales, while acknowledging the strengths and weaknesses associated with each dataset. In addition, they create a subset of adversarial examples with minimal lexical changes that switches the meaning of sentences from sexist to non-sexist.

Furthermore, for the justification of method choice (I.5), the authors rely primarily on a supervised approach. Although implicitly, their argumentation is that only supervised models can replicate human codings that distinguish between different subdimensions of sexism. However, they do not only rely on one specific type of method but rather select a variety of models, such as a Logit model, a CNN and a fine-tuned BERT model with increasing complexity to systematically compare their performance, allowing for a thorough evaluation of measurement performance across different models. Likewise, they also decide to include dictionary baseline models (see the section on robustness checks rerunning the analysis using alternative text-based methods (IV.1)).

For justifying the level of analysis (I.6), they select the sentence level as the unit of analysis, which is aligned with the literature and the structure of the survey items. For the justification of preprocessing decisions (I.7), the authors only provide a detailed description for the Logit model, omitting such details for the other methods.

Filled-Out Checklist

Structural Evidence

To demonstrate structural evidence, Samory et al. (2021) proceed with a combination of validation steps to examine and evaluate the properties of the model and its output. To evaluate the model properties, they conduct an inspection of predictive model features (II.1). To do so, they evaluate the most predictive words for each sexism category (unigrams) and compare them across their data sets and methods applied. Thus, they observe that some models, which are trained on slightly adapted adversarial examples (see Wallace et al. (2019) Zhang et al. (2020)), exhibit more general features, which indicates increased model robustness and, partially, performance. To evaluate the model output, they furthermore conduct extensive error analysis using data grouping (II.5) of misclassified examples to identify systematic errors on their most promising BERT model. They specifically investigate the influence of various factors to assess where the model misclassifies messages using a logistic regression model. Relevant factors which they consider are the type of model used (i.e., whether it was trained on original or adversarial examples), or the origin of the training data. Furthermore, they also evaluate the impact of the initial agreement among the coders on the probability of misclassifying errors

Samory et al. (2021) provide structural evidence by evaluating both model properties and output. They inspect predictive model features (II.1), comparing the most predictive unigrams across datasets and methods, noting that models trained on adversarial examples demonstrate greater robustness. For model output evaluation, they conduct error analysis (II.5) on misclassified examples using their BERT model, examining factors like model type, data origin, and coder agreement to identify systematic errors.

Filled-Out Checklist

External Evidence

To demonstrate external evidence, Samory et al. (2021) primarily rely on the comparison of measures with a human-annotated test set (III.1). To calculate classification performance, they apply k-fold cross-validation and report F1 scores. The evaluation of F1 score is widely regarded as the most viable metric, as alternative metrics such as accuracy (i.e., the overall ratio of positive predictions) can be misleading when dealing with imbalanced data (Spelmen and Porkodi 2018).

Filled-Out Checklist

Besides validation steps that provide validation evidence, Samory et al. (2021) conduct a series of robustness checks, that are further described in the respective paper.

4. Discussion

In summary, ValiText offers a structured and systematic framework for validating text-based measures of social constructs. One of the tools major advantages is the clarity it brings to the validation process, enabling researchers to document and communicate their validation effectively. With well-executed validation, researchers can be sure to identify data quality issues that might affect the validity of their measurement. By providing pre-structured checklists, ValiText reduces the cognitive load on researchers and promotes transparency, offering a uniform way to ensure that all critical aspects of validation—substantive, structural, and external—are addressed.

Despite its strengths, the framework has certain limitations. The primary concern is the reliance on self-assessment tools, which may introduce subjectivity, as researchers might interpret the validation steps in a way that favors their results. To address this, we provide evaluation criteria for each validation step. While these criteria are often implicit, such as requiring the documentation of specific decisions, researchers tend to prefer clear indicators and cut-off values. In this respect, we aim to reference relevant literature to guide these decisions, though this can be challenging. For example, consider the F1 score: values above 0.8 are typically seen as good, while those below 0.5 are viewed as poor. However, interpreting this metric is highly dependent on the construct’s nature and the contextual factors of the measurement design. Therefore, researchers must adapt and interpret cut-off values appropriately, either by comparing them to related work or selecting the best-performing model from several contenders.

Additionally, the rapid evolution of text analysis methods and the frequent introduction of new models and packages present another challenge. With new techniques and tools emerging regularly, researchers may face difficulty in keeping up with the latest advancements or ensuring that their methods remain up to date. One example for this is the emergence of prompt-based classification with the advent of GPT-models. This can create a moving target for validation, as established workflows may not fully account for the capabilities or limitations of new models. Whereas we believe that ongoing effort is needed to ensure the validity of computational text-based measures, we are convinced that our framework provides a solid conceptual foundation for assessing the underlying types of validation evidence.

User Code Database

Meet-the-Experts Video

DOI

References

Footnotes

Nevertheless, it’s important to acknowledge that the “true” nature of a text is inherently unobservable and can only be approximated. For instance, while we might interpret a certain text as positive or negative, these characteristics are not intrinsic to the text itself; they are inferred and open to subjective interpretation (Krippendorff 2009)↩︎

Reuse

Citation

@online{birkenmaier2024,

author = {Birkenmaier, Lukas},

title = {ValiText},

date = {2024-11-22},

langid = {en}

}